GIS projects are often complex animals, involving varied sources of data, project needs and requirements, tools, reports, people, perspectives, and budgets. They typically involve several components, and a group of people possessing diverse skills and specialties which must work together to produce a desired result.

In this technical field it is common for management and project teams to search for expertise focused on a particular task, (such as custom programming), industry specialties or software expertise; sometimes without considering the overall project life span. As an example, you may be required to use GPS based data in a GIS system to deliver a product to your client but may not be sure which GPS tool is best, or how to transfer it to a usable GIS system. It is very common to see PowerPoint presentations and graphic describing “The” GIS project life cycle.” However, real life experience shows that while some standard elements are almost always present, and a sequence of events is needed, it is rare that a project follows a standardized process exactly.

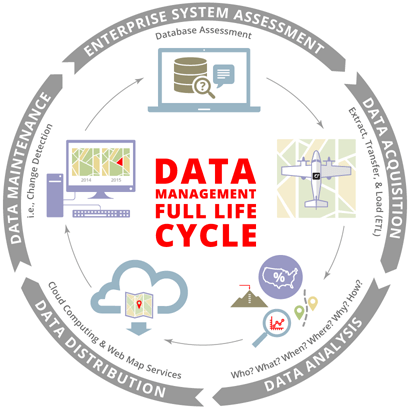

Here are a few examples of GIS Project Life Cycle models:

Some representations are more detailed, but adopt the same circular model:

In all these examples, the process is seen as both linear

(Plan, collect data, map, analyze, etc.),

and iterative, as indicated by the circular motif. Though many people prefer a simply linear,

straightforward project progression, things change, new information becomes

available, and problems arise, requiring that the project “start over” at some

stage of the circular process.

This is particularly true with GIS projects, as data acquisition, QA, and

formatting needs to happen before such steps as mapping, analysis, and

implementation can be done properly. As

such, most projects involve several trips “around the circle,” often with steps

being expanded, passed over or new ones inserted as the work moves along. Still, the circle model is useful and

comfortable, as it provides a generalized picture, and allows for re-thinking

and adapting strategy and activity mid-project.

Of course, there are many other ways to describe a project management process, and these are common across disciplines. The example below shows a different way to look at project implementation, but does not directly address the unique elements of geo-spatial work. Still, it points out that many elements and issues combine to make a successful project happen. In my opinion, geo-spatial folks sometimes miss these seemingly mundane details.

We GIS folks tend to be “data centered.” We have many high-tech tools to gather data, and are sometimes too quick to “get the data, make the map,” passing over more subtle considerations. I am reminded that GPS and GIS are collections of tools to help us gather and explain information, not aims in themselves.

At Synthos, we understand the GIS Project life cycle, in all its permutations. Our experience spans the entire spectrum from Strategic Planning, Needs Analysis, Defining Data needs, through field Data Collection (including all levels of GPS/GNSS survey), analysis, mapping, problem solving, and producing meaningful reports, maps and processes tailored to the specific needs of our clients’ missions. Since no-one can do it all, we maintain relationships with experts in a wide variety of fields to help us develop Project Management solutions for many industries and applications. In fact, we practice good Project Management every day, by assembling our teams on a project needs basis, keeping in mind that process interruptions and data problems can always arise. We start off ready to handle unexpected problems.

If you need a GIS vendor with a broad perspective who can make sure your project succeeds, call Tom Simon, President, Synthos, LLC. 206-406-5246. Leave a message if you need to, I’ll get right back to you.

Or E-mail: synthosllc@gmail.com.